As I’ve studied the polarization problem caused by our endless Culture Wars and the negative impact on both ourselves and our society, I’ve begun asking myself these questions:

How do we engage people who disagree with us, while keeping in mind God’s commandment to love our neighbors as ourselves?

How can we be part of the solution and avoid becoming part of the problem as our society grows ever more partisan and angry?

I’ve decided one of the first small steps I can personally take is to examine my relationship with social media. As I’ve begun doing so, I’ve come to an inescapable conclusion: I need to pay much more conscientious attention to what I post, share and “like” on sites like Facebook and X (formerly known as Twitter).

If there’s one thing many conservatives and progressives agree on, it’s that social media have played a huge role in keeping the Culture Wars going. In one survey by the Pew Research Center (link HERE), 55 percent of adult social media users said they felt “worn out” by how many combative political posts and discussions they see on these platforms.

Seven in 10 respondents also said they found it “stressful and frustrating” to communicate on social media with people they disagree with about politics. The sense of exhaustion and frustration held true across political parties, according to the report.

Several culprits contribute to social media’s role in dividing us. Algorithms that create “echo chamber” bubbles of one-sided information and opinions. Viral spread of false or misleading information in “fake news” stories with click-bait headlines. Political “discussions” that amount to little more than judgmental blaming and shaming, name-calling, insults, character assassination and demonization of opponents. Endless memes promoting hateful and inflammatory messages.

The worst part? I have to admit I’ve been part of the problem from time to time. Too often in recent years, I’ve found myself getting sucked into social media fights – even with people I ordinarily like – over politics and contentious “hot-button” ideological issues.

Whenever a Facebook skirmish erupts – whether the trigger is a Supreme Court decision, a political candidate’s suitability for office, or a crisis playing out on the news – my first instinct is to try and stay out of the fray.

Alas, I tend to have strong opinions about a lot of issues (imagine that!) and sooner or later, someone will post a meme that I just can’t seem to resist sharing against my better judgment. Okay, I know it’s a bit snarky. Maybe a bit judgmental or even mean. But it’s SO clever. Then, of course, someone on “the other side” will beg to differ with my assessment of the meme’s cleverness, and before I know it, I’m bogged down in another argument.

One evening, I realized I had just spent the better part of a whole day arguing with total strangers on a Christian Facebook page over this question: “Is it racist to make jokes about lutefisk, lefse and jello at Lutheran potlucks?” (No, I’m afraid I’m not making this up.) I further realized it wasn’t the first time something like this had happened.

So what can I start doing differently?

I’m not ready to go “off the grid” when it comes to social media. With family and friends scattered over two continents, I would not be able to stay connected so well without Facebook. This was especially true during the recent pandemic.

However, I’ve decided I can take some constructive steps to avoid getting lured into flame wars and to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem when it comes to divisive social media behavior.

I can fact-check articles I want to share before posting them. I personally see nothing wrong with sharing thoughtful, well-researched articles about issues I care about. But I have a responsibility to double-check these for accuracy. Some good sites for fact-checking my sources include Snopes.com (link HERE), FactCheck.org (link HERE) and PolitiFact (link HERE).

I can respect people who don’t agree with me. I’ve learned it’s best to resist lecturing people on their lack of personal integrity or intelligence, even if I think what they’ve shared is just plain wrong. I can’t remember ever changing anyone’s mind about an issue because I sufficiently shamed them. If a Facebook friend posts an inaccurate or misleading article, meme or video, I can skip the snark and simply respond with a link to a Snopes.com article debunking the item in question.

I can practice selective attention. If I don’t agree with someone’s post, I always have the option to keep on scrolling and not respond at all. (What a thought!)

I can set my own standards of behavior for my own posts. When the vitriol starts, I’ve begun deleting comments from people who choose not to respect others, and even blocking some of the worst offenders. I have blocked or “snoozed” both conservative and progressive Facebook friends who insist on insulting my other Facebook friends.

I can be aware of what I enable. What am I encouraging others to post by hitting the “like” button? Am I inadvertently rewarding name-calling, character assassination or polarizing comments?

I can resist “click bait.” Sometimes I can tell from the headline that an article is pure negative spin. (Watch Politician A school Politician B on life in the real world.) Given the fact that clicks generate ad revenue, do I really need to contribute one more click in response to that scurrilous article?

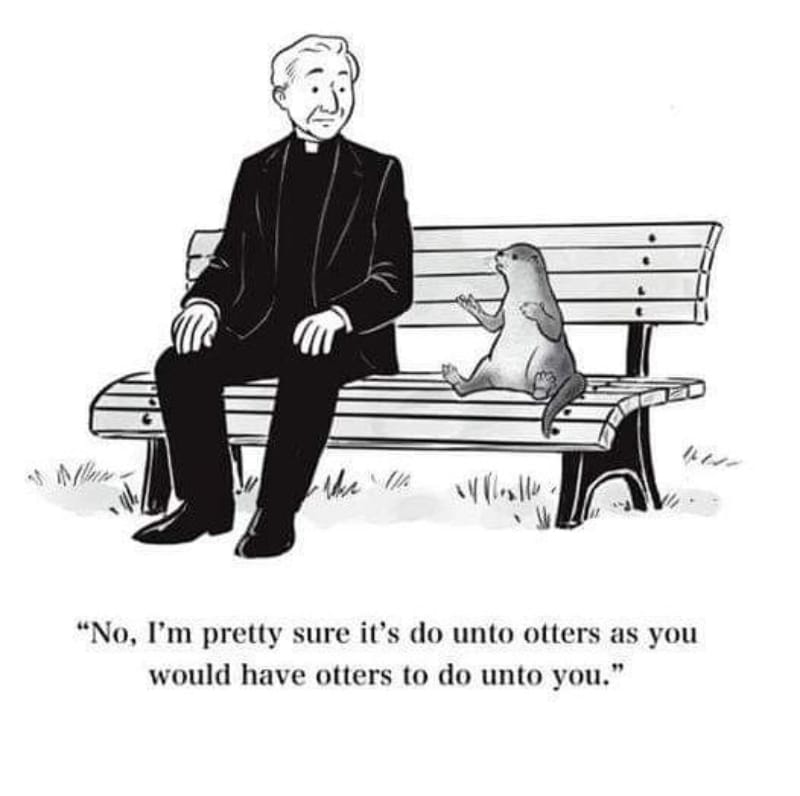

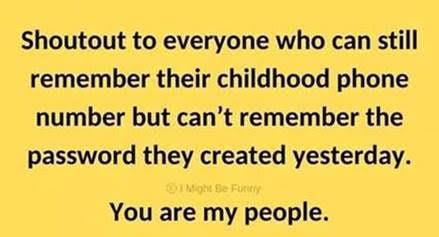

I can avoid using memes to convey complex ideas. One of the problems that keeps us all from resolving issues appropriately is our modern emphasis on brevity. It is nearly impossible to give an issue the depth it deserves when our communication is limited to 15-second sound bites, 280-character tweets, bumper stickers and t-shirt slogans – and all those endless memes.

I can reduce mindless surfing. If I go online with a specific purpose in mind – to check emails, research a blog article or catch up with the latest updates from Facebook friends – and limit my time on social media, I’m less likely to absent-mindedly click on headlines like 21 of the Biggest Political Scandals in History.

Finally, I can use Facebook for its original purpose – to help me keep up with family and friends. How are all my nieces and nephews and dozens of cousins doing? Who’s getting married? Who just had a baby? Which friend got a promotion at work or went on a fabulous vacation? Who just went to the emergency room and needs prayers?

Or I can share cute photos of all the adorable pets Pete and I have shared our home with since we first got married nearly 40 years ago. I’m happy to report I have never had anyone threaten to block or “snooze” me because I posted too many photos of these little sweethearts.

Fortunately, my Facebook friends over the years have loved Elizabeth, Bryce, Champie, Oley, Angie and Torbjorn as much as my camera and I have.

Questions for readers: How has our society’s polarization impacted you personally? (If you live outside the U.S., is there similar polarization going on in your country?) How do we become part of the solution rather than part of the problem? I’d love to hear your responses to these questions, as well as your comments on this article. Just hit “Leave a Reply” below. When responding, please keep in mind the guidelines I’ve outlined on my Rules of Engagement page (link HERE).